Poughkeepsie Journal

In some ways, Alexander Skojec is like any other infant.

He babbles and likes to play patty cake.

But Alexander — who was diagnosed with a serious disorder that makes his future uncertain — is very different from most children. In fact, his disease is so rare that only 50 cases of it so far have been diagnosed.

The 1- year-old child has sialidosis, which means he is deficient in an enzyme that helps break down products so that they can be absorbed into the cells.

For Alexander, the products normally absorbed get stored in the tissues of the body, and that results in enlarged organs and developmental delays.

Dr. David Kronn, a medical geneticist and director of the Inherited Metabolic Diseases Center at Westchester Medical Center, said Alexander was the first case of sialidosis he has seen in his career.

Research Is minimal

How long Alexander will have to live is not immediately, apparent, according to Kronn. “Some patients die in the first year of life, some have a prolonged course,” he said. “Generally, the condition deteriorates over time.”

At A Glance

Sialidosis:

Sialidosis is a rare disorder. It results when there is a deficiency in an enzyme that helps break down products in the body so they can be absorbed by human cells.

Sialidosis is a rare disorder. It results when there is a deficiency in an enzyme that helps break down products in the body so they can be absorbed by human cells.

‘He has the best disposition of any little guy…He is always smiling.’

Instead of being absorbed by the body, the products get stored in the tissues, resulting in enlarged organs and delays in development. Some afflicted with the disorder do not live past the first year of life.

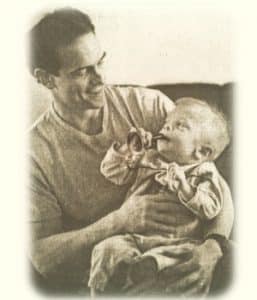

William Skojec, Alexander’s father, is determined to help his son get the best treatment available. But that doesn’t offer much hope since the research for such rare diseases is often minimal.

“There is a whole group of disorders that don’t get any attention that kids die from all the time,” he said. “Since I was somehow chosen for this, I would like to make a difference.”

Skojec has appealed to medical researchers to include sialidosis into their studies and hopes that a doctor in Canada will have a gene therapy ready for a trial within Alexander’s lifetime.

Kronn said that doctors are at the beginning stage of placing the normal gene into a defective cell.

“Everything moves fast in gene therapy,” Kronn said. “There is potential for the future, but it will not happen this year.” Kronn was quick to add that the therapy is only a potential. “We don’t know if it can actually be done,” he said.

Despite the uncertainty, the Skojec family continues to live as normally as they can. William Skojec said that Alexander “can’t do a whole lot” and needs someone to constantly take care of him. Still his father said, “He has the best disposition of any little guy … He is always smiling.”